The Criminal College

Without high-school diplomas and either wholly or functionally illiterate, those typically occupying United States federal prison cells are indeed what L. Ron Hubbard writes of here: students attending the only college that will have them. Moreover, they typically remain faithful alumni—which accounts for America’s “revolving door” prison system wherein the better part of every “graduating class” returns within three or four years for “graduate studies.” Meaning: they’re rearrested to serve even harder time. Hence L. Ron Hubbard’s observation: “The effect of punishment on a criminal is to confirm that behavior, and cause him to insist upon it.” And hence his “The Criminon College” in emphasis of the fact that twenty-first-century recidivism follows from a long and slow failure of the twentieth-century criminal reform. Indeed, the article dates from 1937 and so comprises a root discussion on the evolution of prisons, where inmates are as thoroughly stamped with the imprint of their “college” as any Ivy League alumnus. While upon graduation, and regardless of his particular major, the ex-con is just as prepared “to prove himself worthy of the only fraternity which ever took any interest in him.”

An Essay written by L. Ron Hubbard

THROUGHOUT THIS WIDE LAND, wherever one turns, great piles of sullen stone crouch like traps of some giant’s hewing. But no trap ever possessed as many guardians, and certainly no trap ever occasioned as much oratory as is yearly bleated about prisons.

One of society’s most barbaric survivals, one of the sorriest comments upon the mass of humanity, the prison has been with us since the time the first Eoanthropic chieftain heaved a disorderly dawn man into a damp and inky cave.

Since that time the routine has varied little, enlivened perhaps in this age and that with the addition of torture, but always known by a few unchanging essentials. Any man carries with him his idea of a prison, defining it as a small, poorly lighted cell wherein a person may be restrained from associating with the rest of society.

Considering the very many ways of accomplishing the fact without resorting to that exact means, and considering also that this small, dark cell remains universally basic, it is strange that no one has tried to arrive at the fundamental fact. That fact has always been with us. Perhaps that Eoanthropic chieftain knew, but between his time and ours it is to be doubted that the crude truth has been set down.

And that truth is crude, perhaps, to our Calvinistic society. It would very likely offend many minds which care more for the conventions than for either truth or the general good.

But it can be very simply stated. And perhaps because it is so very simple, great psychiatrists and criminologists have cared to overlook it.

The sentencing of a man to prison is the combined wish of society that that man be returned to the womb from which he came. It is the mass regret that that man was ever born.

And as long as society indicates that desire, the courts and officers of the law will continue to obey the rule of the multitude and wish, in very serious forms with a very pompous air, that same fact.

“You are hereby sentenced…” might well be translated into, “You should never have existed in the first place.”

In the enlightened barbarism of our times, there are those with wit enough to see the stupid fallacy of this. The analogy between a small, dark cell and the womb seems to have escaped the attention it deserves. But it is no interesting little fact like those so dear to Ripley. It is a mountain of facts which would take a century to untangle.

There is the criminal, standing before the so-called bar of justice. He is a human being with head and arms and legs. He is the fait accompli. There is no use wishing that his father had been more careful. There is no use deploring the fact that nature gave him oxygen to breath and food to eat.

But still, society wants no more of the fellow. Obviously there is only one thing to be done on the face of it, only one wholly sensible thing. Kill him and let the ministers wonder vaguely if he ever had a soul. However, the crime was not that great. The judge wishes to be rid of him for only a short time, supposing in some lofty and doubtlessly marvelous process of reasoning that a few years in the cell will allow the fellow to again be born as a completely different person. It is to be wondered, then, why judges seem forever angered when the same fellow, five years later, again stands before the bar of justice awaiting another, “Society wishes you had never been born.”

The masses, whose will the judge executes, have contrived to remain astonishingly in the dark along with most of their psychiatrists, about a host of facts emanating from this rather indecent wish.

The individual man thinks of a cell simply as a place where the criminal will be held incommunicado until he is finally reborn. It rarely occurs to this individual man that he is actually fostering the practice of placing this one criminal in the society of criminals. That the single criminal contacts very few of his fellow felons outside the prison walls, never seems to have any bearing on the situation.

It is not a new thought that the criminal meets many of his kind in prison and learns from them many things which he before but dimly suspected.

Many men in many offices under many chiefs have been busy for many years compiling crime statistics. It is doubtful if the tabulated results are meant to bring any more order into the world. The numbers and percentages are mainly intended to show the public that men are actually tabulating such things and that, therefore, much thought, energy and result is being obtained and hoarded in return for certain salaries to be paid out of the public treasury.

That something can be done with those figures seems obvious enough. Then, it would seem to follow, why isn’t something done?

We learn, roughly, that the criminal of today, by a large majority, ranges between the ages of twenty-four and eighteen.

By applied humanity, perhaps it is possible to understand why a boy at eighteen will turn to crime. Is it possible that it is directly related to the wish of society that he has never been born?

Oh, certainly not that! It is much too obvious. These things must be couched in polysyllabic sentences by men so overburdened with degrees that they wear out ten pens a day signing their names.

Certainly there can be no foundation for the idle statement that all true things are the easiest.

But, just suppose that there is some truth in this. The individual man looks hazily at the rest of society. To himself he is clear and important and very much a unit. But in a haphazard way he believes that all the people around him are different than he. They are all tied together and he is the only person in the world who is wholly alone.

And because he must live in his own flesh house for more or less three score and ten, he knows he will have to associate with a tyrannical mind perilously close to the end of his nose. Therefore, he never blames himself for anything. If he sinks a hatchet into the head of his firstborn, strangles his wife, rapes the lady of his best friend and then embezzles the funds of his firm for the getaway, he utterly believes himself when he tells the world that he is being oppressed.

If she takes out her husband’s new car and dents a fender putting it back in the garage, she soars into a tantrum, throws things and feels very abused if her husband mildly cautions her to be more careful next time.

What, then, is the thought process of an eighteen-year-old boy when his elders show such astonishing lack of good sense?

He was placed, at the age of five, in a school. And there he was taught, along with his alphabet, that he would grow up to be an important citizen in this world.

At home he is usually expected to amount to something when he “grows up.”

He carries this innocent-appearing virus with him into his teens and, finding himself close to manhood and an important seat in the sun, he allows the germs to breed beyond all hope of inoculation against them.

And then at sixteen or seventeen or eighteen, uncouth truth rises like a concrete wall before him and he runs into it and bruises himself.

Experience, in a gagging dose, has informed him that there are only two people in the world who care whether he lives or dies. But he cannot always lean back upon his father and mother for the necessary feeling of importance.

Then comes a variety of things, never identical from case to case. A third person makes eyes at him and he wants to have money, which is denied him through the regular channels because the world does not care to give him a job. He wishes to appear important or daring among his fellows. He has a real, crying need for money and is hungry or cold.

That is the extent of his criminality at the moment. He is young and has therefore not had a long and battering experience to tell him that the easiest money is to be gained by the hardest sweat. He is not thinking of himself as a collective piece of society. He is an individual and needs something.

It is easy for him to credit himself with greater cunning than he actually possesses. After all, he knows nothing of LAW. He has heard of fingerprints only in a detective story.

Very well, the world has defaulted. He has been gypped. The job he was always led to believe he would get was only a mirage. Therefore everything else is a lie and society is bad in that it gives never a damn what happens to him as long as he stays out of the way.

Combined with that, he is bored. Life, he does not know, is a very drab and dreary affair as long as man stays on the wide but crowded sidewalk. Thus he steps out and commits his first crime. His hand is shaking so he can’t see the front sight of his rusty .22 pistol. He can only hear the roar of blood in his ears and sounds which were never sounded. He forgets where he should look for the money. He makes too much noise. He can’t control his voice.

Gasping with nervous exhaustion he runs away and behind closed doors stares at the few tattered bills. Still, they are his by right of possession. In getting them he has obeyed a natural need for excitement or food or clothing or that necessary front before his girl or his friends.

And now comes the deciding factor in his life.

The police either catch him or they do not. If he eludes them he may try another “job” or two, emboldened by his first success. But in an astonishingly short space of time he will run up against a “tough one.” In a stickup of park spooners, the man tells him to go to hell and grabs for the gun; the youngster gets away and vows to stray no more. In a filling station, the attendant reaches for a wrench and again the youth flees in terror. In a majority of these cases, the youngster thereupon lays away the .22 forevermore and a few years later looks back with a private grin and perhaps even an uneasy twinge about his “crime career.”

If he is caught, he is doomed. Standing soaked with nervous sweat, he looks up at the judge in a black robe remarkably like a vulture’s rusty wings. The youth is actually hearing, “You are hereby sentenced…”

As soon as he can bring himself to believe that this is really life and not a nightmare, he begins to believe the words really were, “Society wishes you had never been born.” Not in those actual words, of course. But the feeling is there.

From the time he began to think about crime until now, the thought that the world did not want him was but partly felt. The whole impact of that truth strikes him now.

Society does not want him. He was right!

In a most lofty fashion, a judge on a bench, wondering what his wife will have for dinner, has completed the metamorphosis of the youth’s ideals.

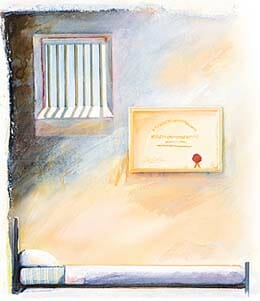

He is a ripe freshman for the Crime College. No professor of hooeyology was ever confronted with such an ardent student.

In the big, sullen pile of gray rock, the youth discovers that there is a strata of society which actually wants him. He has never seen a real criminal before and the actuality awes him. He hears men talk pridefully of stickups. He receives the usual treatment meted out to all freshmen. He’s small time.

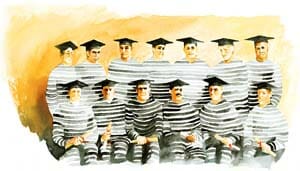

Through the courtesy of the state, in penitentiary or reform school, the youth receives a thorough working over. By the time he graduates, his life work is definitely planned for him. He is a snow-eater or a pervert or a tough case, but most certainly ready, in most instances, to prove himself worthy of the only fraternity which ever took any interest in him.

There comes a second crisis in his life.

On his first half-dozen jobs with the friends of his friends, he must assume the most dangerous posts and missions. Therefore he stands an excellent chance of being either shot down or picked up by the vigilant, brave and intelligent police.

Should he come through this test by fire, he is a wiser man. And as war develops cunning in an “individual fighter” so that he outlasts the rest of his company under any conditions, so does experience serve as a shield for the by now hardened criminal.

Quite naturally he follows the only profession in which he ever had a thorough training. No matter how many times he is caught, his sense of importance forbids him to think that it will happen again. That he is caught, again and again, is inevitable, just as inevitable as the fact that a parole board will turn him loose.

He returns to jail as a graduate returns to his alma mater, and there is more truth than wit in that. It is most amazing to listen to these men sit and exchange notes.

“Thirty-three? Yeah, I was in Leavenworth. Jimmy Fenton was there.”

“Was he? Well, I’ll be damned. Him and me were in Alcatraz. We had a tough screw there…”

And equally astonishing is the appearance of these fellows. One kindly old gentleman had an extensive enough list of “jobs” to send him to four leading penitentiaries.

It is an unhappy failing of the Anglo-Saxon to insist upon a solution being presented with every advanced problem.

There are many more solutions that the easy, stumbling, stupid one of sending a youngster in his teens to jail. There are enough such solutions to fill an encyclopedia. But so educated or uneducated has the human race become that the return-him-to-the-womb wish predominates to such an extent that most men are unconscious of any other solution.

Let it suffice to say that discipline instead of criminal education via the prison has changed the destiny of many more men than are willing to admit it.

One youngster, at the moment, serving four years in the United States Marine Corps (USMC), started his crime career stealing cars and generally annoying the police and public. A judge told him that he would either get two years in the penitentiary or four years in the Marines and for him to take his choice. As a marine he has an unblemished record, has risen by his intelligence to be a corporal and when last seen was studying diverse matters concerning useful endeavor in the civilian world.

The USMC will probably rise up to a man from the dawn to the setting sun to condemn that exposure. Not many youths have had the luck of that corporal and the cases are pitifully few where a youth had a chance to choose. The corporal had a few tough sergeants at Paris Island [Marine Corps Base] to take all the nonsense out of him and he emerged a healthy, straight thinking fellow.

There is also the prison colony system, so regrettably abused by France and England. The failure of the prison colony does not lie in its principle but in its application. A sane man will turn mad in French Guiana, even if he be “free.” No human being could survive the jungles of Tasmania when natural hazards are supplemented by overlord keepers with shoot-to-kill orders and unhealthy appetites of their own. There is one prison colony which did survive to a remarkable degree. But the word must be whispered as it is today, though first settled by “criminals” the most crime-free continent in the world – which would seem to dispose of the heredity theory.

There are more roads to be built, more dams to be raised in these United States than a hundred million men could finish in a thousand years. This implies criminal labor. But is criminal labor to be judged and discarded without a second thought when the conditions under which it is practiced rival French Guiana?

Can a man keep his self-respect when he is chained by the ankle to his fellow? When a guard stands near with a gun? When no thoughtfulness is shown to him? And last and most important, when his work is labor, not accomplishment?

There is Alaska, a land of great opportunities but seemingly in great need of a population and willing workers.

Ah, no, I venture upon dangerous ground.

Of course the only system is to wish that the malefactor had never been born. The mere fact that he is born and has grown to man’s estate has no bearing upon it whatever.

Naturally we actually care very little about who forms the rank and file of organized crime. We don’t give a snap of the fingers if our house is robbed or our child kidnapped. Why shouldn’t we board and room and pay the tuition of youngsters in the College of Crime?

One small fact, if proved, will have no possible bearing upon the situation: If the number of criminals within our boarders has decreased since the formation of the CCC, duly allowing for the natural increase in all ranks of crime bred by the humility of relief and the increased need and suffering of families everywhere.

No, that would have nothing to do with it whatever.

We, the people, plead, beg, demand that the practice of wishing stumbling youth had never been born retain its honorable position upon the unquestionably accurate law books of these great and glorious United States, the land where all men are created equal.

– L. Ron Hubbard